Labour is in short supply everywhere. Nestor, a skills platform provider, says that “unlike other trends in the world of work, the skills shortage is not just a buzzword but a reality (that is) already affecting various industries and regions, with the potential to impact the global economy itself in the near future”. ONS data reveals that “nearly one-third of UK businesses are experiencing labour shortages after an increase in economic inactivity post-pandemic. The number of workers has declined by 545,000 in what has become known as ‘the great resignation’, a drop that has worsened inflation and limited public service funding.”

Skill sets

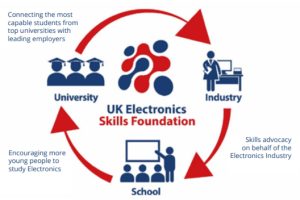

In some areas this manifests as longer construction times or increased waiting time in restaurants. The electronics manufacturing world faces the same challenges, and much effort and publicity has rightly been given over to the importance of STEM education. However, there is a further hidden problem. While schools and universities are placing huge emphasis on achieving engineering qualifications that will produce the next generation of design engineers, there is little consideration for industry’s need for technicians. Our educational establishments do almost nothing to promote trade skills. The attitude seems to be if a young person is not good enough to progress as an engineer they are not being encouraged into the industry at all.

There are, of course, some apprenticeship schemes, but training providers are not really seeing young people coming into the industry. Instead, companies are mainly recruiting people from other fields, in the hope that they have transferrable skills and can be trained to be competent.

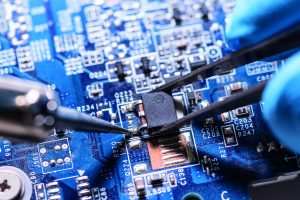

On the plus side, pay at an electronics manufacturing company is much better than, say, a franchise restaurant. Trainees have included those who have previously been flipping burgers or stacking supermarket shelves, as well as those who have worked in the automotive and other manufacturing sectors. It is very often the case that the people being trained have been in their current position with an electronics manufacturing company for only weeks or a couple of months. Courses designed to achieve IPC certification are often combined with bespoke training, providing a basic understanding of the soldering process.

Certification vs competence

It is important to explain the difference between certification and competence. Even with a course that includes a practical element – such as the IPC’s J standard – certification means that the person has attended the course, received the specified training and achieved a certain level of performance.

Many employers assume that this means that the person can then be let loose on any soldering task required. That is not the case. They will need experience, further instruction and mentoring to become competent. A comparison is learning to drive. Putting on L plates, taking lessons from an instructor and passing a test does not make you a good driver. It does, however, mean you know how to operate the car and can perform certain tasks to a minimum level. To become a good driver – or a competent soldering technician – it is necessary to have performed the task many times under the guidance of experienced co-workers and supervisors.

The value of IPC certification is that it demonstrates that a company has not only trained its technicians, but that they have been trained to a standard. It increases a technician’s confidence that they are doing tasks correctly. It may mean that a company can increase the services it offers and/or offer those services to sectors that are more demanding, for example defence. It is important to bear in mind that the trainee technician is going to require further and ongoing training and practice before they are competent.

There are different levels of IPC training: a certified IPC specialist (CIS), a certified IPC trainer (CIT), a certified standard expert with knowledge of a specific IPC standard or group of standards, and a master IPC trainer (MIT). IPC CITs are commonly employed at a company to train its staff with the skills they need on a day-to-day basis, often for specific products or contracts. An MIT can train CIT and CIS staff and provide their technical support. There is a separate MIT credential for each IPC programme.

IPC certification belongs to the individual, not the company, however, and there have been instances of operatives receiving training, then using that certification to get a better paid position elsewhere. This situation is always exacerbated when there is a labour shortage, but some companies have taken the disappointing step of not getting their technicians certified. An individual can always independently become IPC-certified – a two-day basic level course is generally affordable and comparable in cost with other professional qualifications.

Job fairs

ART, in conjunction with the IPC and Nano Electronic Services, held the first Insight into Electronics Manufacturing Workshop & Job Fair in Redditch (UK) in March. More are planned for later this year. The job fair is designed for local electronics businesses to showcase themselves and promote any current vacancies, while the workshop includes discussions around opportunities available in the electronics sector and how people can benefit from a career as an electronics technician.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News