Education matters at all levels: there is a real disconnect between the technology that young people use and the realisation that they can be creators of it (Image: Shutterstock)

Imagination Technologies has published a white paper identifying the key challenges facing the UK. Top of the list is a “skills shortage in the technical and professional skills needed to power the knowledge economy”.

A recent survey of UK business leaders found less than one in five (18%) believe that school‑leavers and graduates have the right digital skills and experience, says Simon Beresford‑Wylie, Imagination’s CEO, quoting Deloitte’s 2019 Digital Disruption Index.

Accenture’s 2018 It’s Learning, Just Not as We Know It report warned that the UK could be one of the G20 countries that loses out on up to $8.8tn in GDP growth from intelligent technologies over the next 10 years, as virtual reality (VR), artificial intelligence (AI) and automation become part of the work landscape.

“The UK can emerge as a global digital skills leader with investment in digital skills”

Simon Beresford-Wylie, CEO, Imagination

“Investment in digital skills will be essential to seizing these opportunities while ensuring that the transition is as smooth as possible. Moreover, in an economy increasingly characterised by insecure and short-term employment, jobs based on in-demand digital skills promise greater job security and income growth. To fulfil its potential in the next phase of technological revolution, the UK must turn the page and emerge as a global digital skills leader,” says Beresford‑Wylie.

Image revamp

For Imagination’s chief of engineering, Tim Whitfield, engineering needs an image revamp. “We need to make engineering credible as a career,” he said. He wants to see a shift in emphasis to the positive outcomes enabled by technology. “We solve environmental issues, we solve communications issues,” he says. “Chip design, low level software, security, low level ethics as AI accelerates are all really important – but how do we teach that alongside web development and coding?”

Engineering needs an image revamp to make it a credible career choice

Tim Whitfield, chief of engineering, Imagination

Whitfield is also keen to “tap the rich seam of talent that doesn’t go through the university route” and to make sure that teaching is relevant to life skills. He relays anecdotes of career advisers turning people away from engineering without understanding what a career in that field involves. He recalls blank looks or comments such as “I don’t like physics”, but when he explains that engineers create communications solutions, then people get interested.

The UK leads in genome sequencing and vaccinations, but for global technology hubs, people look to the US, Taiwan and India. “We need to incentivise – especially in applied engineering – and make sure teaching is relevant to life skills,” he believes.

Enterprise-education collaboration

Working with schools and universities to introduce being an electronics engineer as a positive career choice is one way to address the issue.

Education and enterprise can work together to identify people with potential

Margot james, executive chair, University of Warwick

Margot James is executive chair at the University of Warwick. She was Minister for Digital and Creative Industries (2018-2019) and parliamentary under-secretary for small business, consumers and corporate responsibility (2016-2018).

She says that SMEs generate the majority of wealth in the UK but two thirds lack confidence with digital capabilities. “This underlines the point that you cannot address and improve the digital skills gap by concentrating on education, you have to look at supporting and re-skilling staff throughout their careers,” she says.

Further education provision is “patchy”, says James. She criticises the government’s approach of selecting the top performing further education colleges and giving them resources to create technology departments. “The government should do less but put more behind what they do, rather than scatter funding across projects,” she suggests.

Her ideal engineering apprentice route would be modelled on that of medical doctors, where training is given and continues in early years of practising. In the technology sector, knowledge is rapidly superseded, she says, and this is a justification for continuing education with qualifications.

Local heroes

The more local the impetus, the better the outcome, says James. She cites the example of the National Autistic Society which is training young people in the skills required by the cyber security industry.

Code4000 is a charity which since 2016 has been teaching UK prisoners to code and prepare them for work in the technology sector on their release. As well as providing sought-after skills, the project helps offenders back into society. None of the project’s graduates have reoffended whereas typical reoffending rates are 46% within one year of leaving prison, rising to 60% for those sentenced to less than 12 months.

James cites the collaboration between the University of Warwick and Jaguar Land Rover as an example of a success between education and enterprise. This project, around the electrification of vehicles began with 25 software engineers and now has 2,000. It uses digital skills for specialisms required in the real world, such as the need for a battery industry to realise net zero operations.

The government can legislate for net zero but it can only count as a British success story if batteries are manufactured in the UK, she argues. She points out that the UK lags behind several countries, including the US, Germany and Poland, with gigaWatt factories producing batteries.

This, and the work of the Faraday Institute, which specialises in skills needed for the battery sector, provides answers to real world problems. “These are not just broad brush digital skills but specialisms,” says James. “We need to get education right to meet that capability.”

Diversity as a business plan

Another challenge identified in the report is a lack of diversity in the industry.

“Approach diversity like a business plan, with an action plan and targets”

Kay Hussain, chief executive, WISE

“This should be treated as a business improvement plan, with an action plan and targets,” advises Kay Hussain, chief executive of Wise (women in science and engineering), which campaigns to encourage women to enter STEM-related careers.

“Making it a business case concentrates on the value that diversity brings and will give companies the impetus to change,” she reasons. “Companies wanting to attract funding will need to address this now,” Hussain believes.

She has two teenage daughters and has noticed that they do not relate to a career in any form of engineering because they do not identify with any engineers. “There is a real disconnect between the technology they use and the realisation that they can be creators of it,” she observes.

She believes that technology needs more relatable role models to be able to say ‘this could be a career for me’. She advocates that schools, colleges and universities have a role to play in showing how stem subjects can pave the way to engineering careers. There are, she adds, lots of career paths that take students without maths or physics A-levels or university degrees.

“Diversity expands knowledge and brings perspective,” she says, yet companies are losing out on these because two thirds of female stem graduates do not progress in their careers. She wants to see return and retraining programmes to combat the regression of women in the industry.

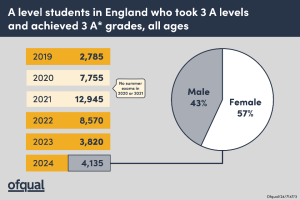

Figures show that girls outperform boys in A-level results. Analysing the breakdown of subjects, Wise found that girls had advanced in computer science by 22% year on year but still only made up 14% of A-level entries for computer science.

In 2015, research by Allison Master, Sapna Cheryan, and Andrew N Meltzoff, published in the Journal of Educational Psychology, showed the importance of ‘allowing’ girls to ‘feel they belong’ in engineering environments. They found that girls walking into a computer science classrooms that had science fiction posters on the walls and electronics objects on display expressed less interest in taking computer science as a subject than girls who walked into a computer science room with art posters on the walls and general interest books on the shelves.

The different environments did not affect the levels of interest expressed by boys. Master, Cheryan and Meltzoff wrote: “Girls may avoid computer science courses because current prevailing stereotypes of the field signal to them that they do not belong. However, providing them with an educational environment that does not fit current computer science stereotypes increases their interest in computer science courses and could provide grounds for interventions to help reduce gender disparities in computer science enrolment”.

Tim Whitfield sums up the challenge faced by the UK engineering sector today: “We need a diverse and highly skilled work force. It is important to engage young people and that companies engage them at an early age and make people understand what [engineers] do”.

The long and short term nature of some of these projects means that their effects may be seen at different times, but the drive to achieve change across the industry seems to be gaining momentum.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News