Diverse women mates business team look at computer discuss review project solve common issues, do task, learn new corporate e app. Cooperation, mentoring, brainstorming co-working co-workers concept

There has been a 61% increase in jobs in the IT sector in the past year (source: Keep Britain Working), highlighting the demand in the sector, as well as a need for new talent. While this may seem like good news there is an issue: the lack of diversity in the workforce.

Gender equality

Only 19% of the technology workforce are women (according to Tech Nation), and 77% of technology director roles are filled by men. Women hold 26.5% of executive, senior level and management positions in S&P 500 companies, a figure matched or exceeded by many technology companies, but one that is still far from equality.

Disparity also extends to ethnic minorities – one of the most prominent issues in the technology sector – as only 4% of the UK tech workforce is black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) in the UK (source: WSH Recruitment). Research has also shown that ethnic minority workers are paid around 10% less than their white colleagues and only one in nine senior leaders in the industry comes from a BAME background.

Why the problem starts at school

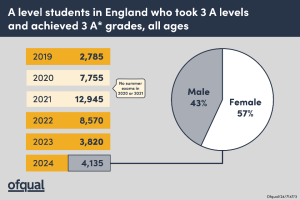

To learn why the technology and computing industry struggles so much, we have to look to the root cause. Statistics show that females tend to perform – on average – better than their male counterparts at school, yet are still outnumbered when going to study in further education. Just 35% of higher education students taking STEM subjects are women; computer science has one of the biggest imbalances between genders, 81% of students are men (source: STEM Women).

One issue is that traditional career routes into the sector reinforce industry stereotypes – whether gender, age, personality – where in truth, anyone can do any type of job if they have the relevant qualifications or skills. In order to attract a diverse range of talent to the industry, education institutions need to try just as hard as technology businesses to welcome all types of students.

Deferred education

Only 13.3% of undergraduate entrants in 2019-20 were from an Asian background, 9.7% were black, 4.8% were from a mixed ethnic background and 2.2% were from other minority ethnic groups. Students from ethnic minority backgrounds are woefully under-represented in higher education, making up around 25% of the total student population for that academic year.

Typically, those from under-represented or disadvantaged backgrounds decide to go to university later in their life. This is usually because they focus on other commitments such as needing to care for their family (sometimes financially), or are first-generation students and have less support and guidance to continue their education. Later, they may find they have the time, experience, money and understanding to consider working towards a degree.

Typically, those from under-represented or disadvantaged backgrounds decide to go to university later in their life. This is usually because they focus on other commitments such as needing to care for their family (sometimes financially), or are first-generation students and have less support and guidance to continue their education. Later, they may find they have the time, experience, money and understanding to consider working towards a degree.

Older students are more likely to be from under-represented or disadvantaged groups. Research by Million+, the Association for Modern Universities, and the National Union of Students shows that mature students are more likely to be black, Asian or minority ethnic, have known disabilities, and have more non-traditional qualifications than younger students.

How can universities help to close the ethnic disparity? They should appeal to mature students and to a wider range of students. For example, allowing flexibility to cater to them is wise. Giving students the option to pause their education journey, without having to wait until the start of the new year to resume, is the ideal universities should be moving towards.

Higher education systems need to devise courses that are more welcoming to under-represented demographics. Grants and scholarships are helpful, but flexibility and a willingness to be less rigid with traditional forms of assessment and applications are good ways to begin. To open up courses to the array of expertise and intelligence among us, universities need to make sure their way of assessing truly captures the different skills many possess.

This can be done by looking at professional experience or by using practical assessments rather than essays and judging based on theoretics. In other words: let’s actually do computing; let’s not just talk about it.

Soft skills

IT and computing schools should also be responding to the shift in demand from the technology sector. More and more companies are looking for soft skills, such as interpersonal or communication skills, rather than practical skills.

Opening up modules and courses to cover these will make students more attractive for future jobs – inside and outside the technology industry. Practical skills can always be taught afterwards, and many companies are now willing to pay to train the candidate that has the right soft skills.

In addition, providing work experience to women and minorities, or getting them to participate in lectures and events, will strengthen awareness and encourage others to pursue a career in tech. A big barrier that many women in tech and minorities face when it comes to climbing up their career ladder is that they do not see many examples of other people who look like them or share a similar background succeeding in the same field or at senior levels.

By ensuring all students have these foundational sets of skills and by exposing them to the possibilities the sector can offer, we may find the disparity in the technology sector slowly decreasing.

Most importantly, the sector needs to start from the bottom: when students are still at school. If there is no change reflected here, we may well see the technology industry struggling to be truly diverse for a very long time.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News