“Accurate navigation becomes a challenge in real-world scenarios when GPS signals are unavailable,” says Sandia scientist Jongmin Lee.

In a war zone, these challenges pose national security risks, as electronic warfare units can jam or spoof satellite signals to disrupt troop movements and operations.

Quantum sensing offers a solution.

“By harnessing the principles of quantum mechanics, these advanced sensors provide unparalleled accuracy in measuring acceleration and angular velocity, enabling precise navigation even in GPS-denied areas,” Lee said.

Typically, an atom interferometer is a sensor system that fills a small room. A complete quantum compass — more precisely called a quantum inertial measurement unit — would require six atom interferometers.

But Lee and his team have been finding ways to reduce its size, weight and power needs. They already have replaced a large, power-hungry vacuum pump with an avocado-sized vacuum chamber and consolidated several components usually delicately arranged across an optical table into a single, rigid apparatus.

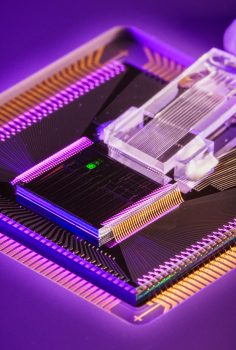

The new modulator is the centerpiece of a laser system on a microchip. Rugged enough to handle heavy vibrations, it would replace a conventional laser system typically the size of a refrigerator.

Lasers perform several jobs in an atom interferometer, and the Sandia team uses four modulators to shift the frequency of a single laser to perform different functions.

However, modulators often create unwanted echoes called sidebands that need to be mitigated.

Sandia’s suppressed-carrier, single-sideband modulator reduces these sidebands by an unprecedented 47.8 decibels — a measure often used to describe sound intensity but also applicable to light intensity — resulting in a nearly 100,000-fold drop.

“We have drastically improved the performance compared to what’s out there,” said Sandia scientist Ashok Kodigala.

Besides size, cost has been a major obstacle to deploying quantum navigation devices. Every atom interferometer needs a laser system, and laser systems need modulators.

“Just one full-size single-sideband modulator, a commercially available one, is more than $10,000,” Lee said.

Miniaturizing bulky, expensive components into silicon photonic chips helps drive down these costs.

“We can make hundreds of modulators on a single 8-inch wafer and even more on a 12-inch wafer,” Kodigala said.

And since they can be manufactured using the same process as virtually all computer chips, “This sophisticated four-channel component, including additional custom features, can be mass-produced at a much lower cost compared to today’s commercial alternatives, enabling the production of quantum inertial measurement units at a reduced cost,” Lee said.

As the technology gets closer to field deployment, the team is exploring other uses beyond navigation. Researchers are investigating whether it could help locate underground cavities and resources by detecting the tiny changes these make to Earth’s gravitational force. They also see potential for the optical components they invented, including the modulator, in LIDAR, quantum computing and optical communications.

“I think it’s really exciting,” Kodigala said. “We’re making a lot of progress in miniaturization for a lot of different applications.”

Lee and Kodigala represent two halves of a multidisciplinary team. One half, including Lee, consists of experts in quantum mechanics and atomic physics. The other half, like Kodigala, are specialists in silicon photonics — think of a microchip, but instead of electricity running through its circuits, there are beams of light.

These teams collaborate at Sandia’s Microsystems Engineering, Science and Applications complex, where researchers design, produce and test chips for national security applications.

“We have colleagues that we can go down the hall and talk to about this and figure out how to solve these key problems for this technology to get it out into the field,” said Peter Schwindt, a quantum sensing scientist at Sandia.

The team’s grand plan — to turn atom interferometers into a compact quantum compass — bridges the gap between basic research at academic institutions and commercial development at tech companies. An atom interferometer is a proven technology that could be an excellent tool for GPS-denied navigation. Sandia’s ongoing efforts aim to make it more stable, fieldable and commercially viable.

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News

Electronics Weekly Electronics Design & Components Tech News